Observational Signatures of the Gas In and Around Galaxies

A summary of my MPhys project at the University of Edinburgh.

By Evan Jones.

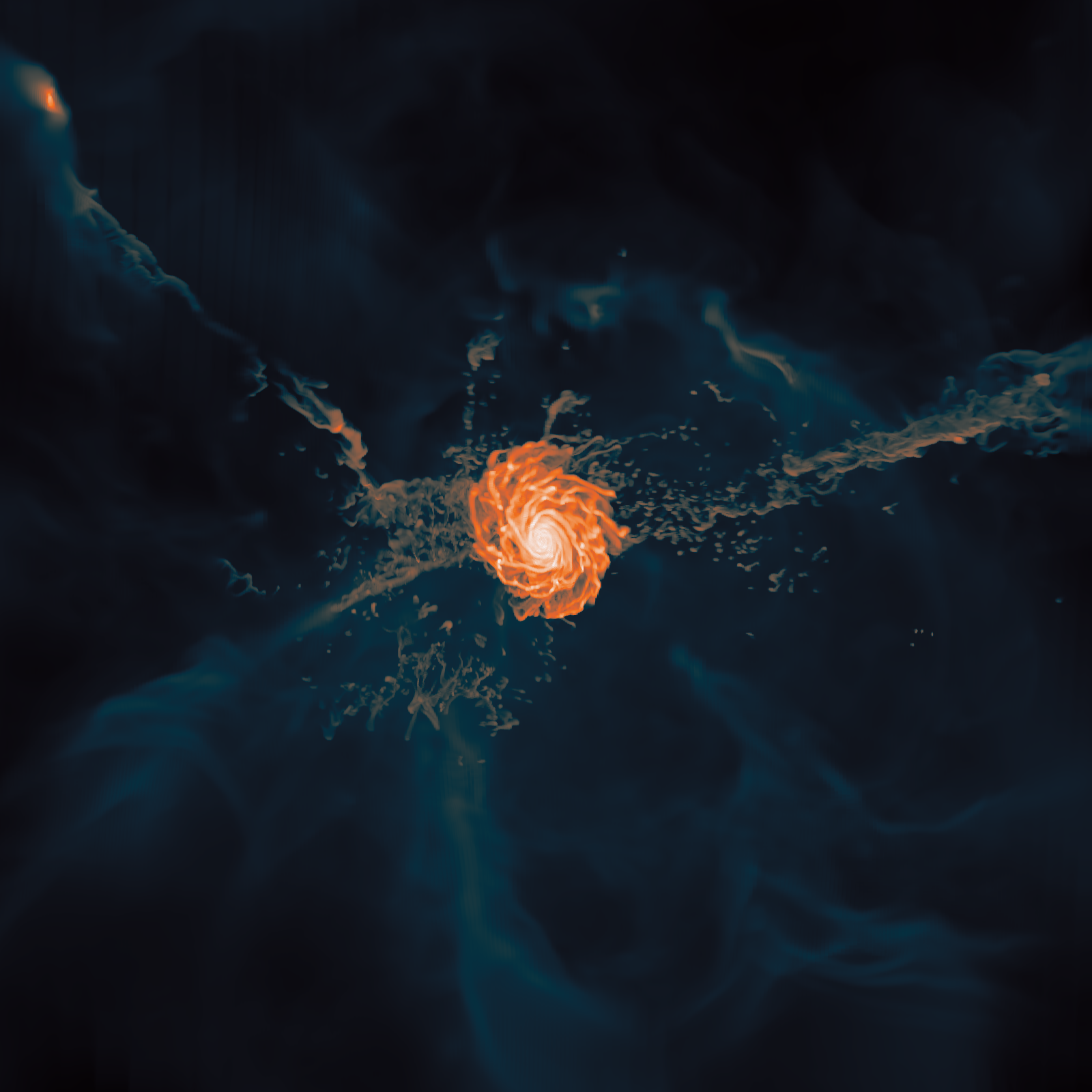

A galaxy can be defined as a large amount of gas and stars held together by gravity. Using our Milky Way as an example, they might have 100 billion stars, making up 4% of the total mass. Gas, mainly hydrogen and helium, makes up another 12%, with the remaining 84% being the elusive and infamous dark matter (see here for a fun visualisation). On top of the enormous amount of stuff to model, the scales that need to be modelled are vastly different. There is no well-defined edge to galaxies, but they stretch out to millions of light-years, the distance light travels in a year. For comparison, the Sun and Earth are 8 light-minutes apart, and Edinburgh and London are ~0.001 light-seconds apart. Processes on 'small' scales, such as how stars heat up their surrounding environments, will have an effect on the galaxy as a whole.

The large difference in sizes and complexity of the processes involved is why it's necessary to model galaxies with simulations, such as those ran by the FOGGIE project. The process of modelling a galaxy on a computer is a balancing act between making enough approximations that the program runs in a reasonable time, but not so many that the results become inaccurate.

The aim of my masters project was to investigate an improvement to these simulation methods, specifically how we model how much of an element is in a given ionization state.

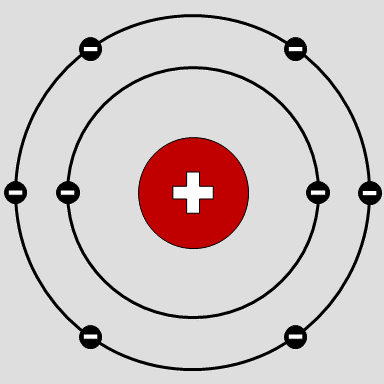

The ionization state of a particle refers to how many of the electrons surrounding the nucleus have been ejected. When an element is neutral the number of protons in the nucleus and orbiting electrons is the same, as they are attracted to each other. Atoms are ionized when electrons have the energy to overcome the attraction, leaving behind an ion. There are two ways to provide the electron with enough energy to escape:

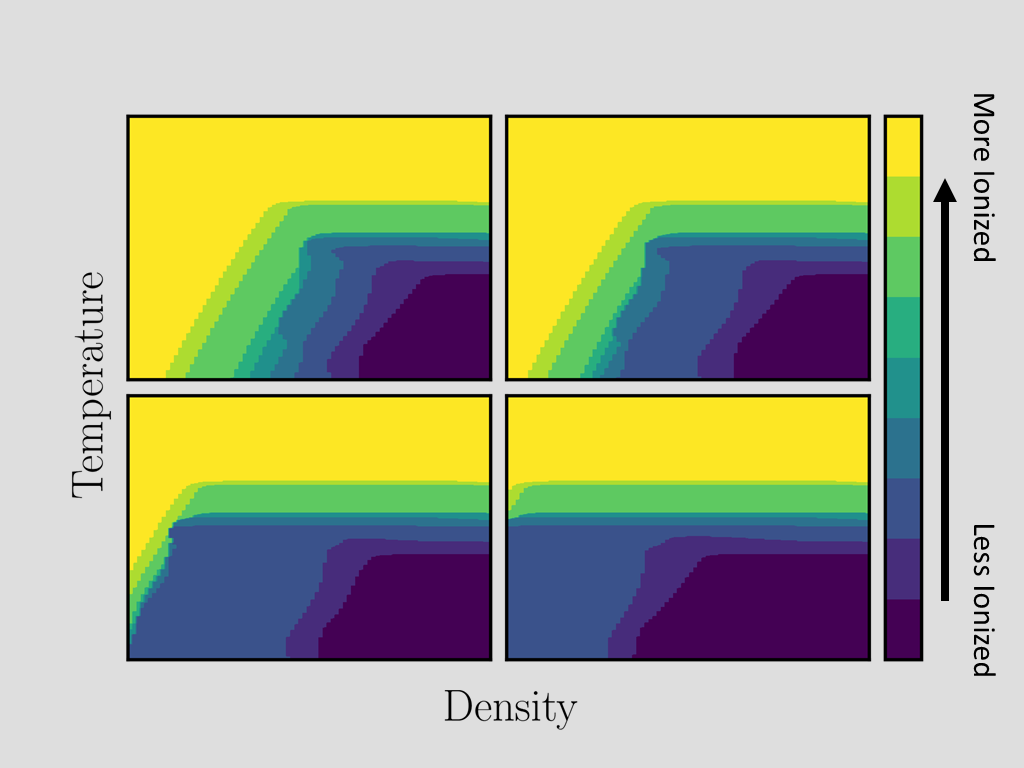

My project focused on how the ionization state of gases changes with the metallicity—the proportion of elements that are heavier than helium (which astronomers refer to as 'metals'). Increasing metallicity means that the cloud is able to absorb more light, because metals have more electrons and as such can absorb more photons. If the outside of a cloud of gas can absorb all the light shining on it, then the inside doesn't get any (called self-shielding), and following from the 2nd point above, the ionization state of the cloud is lower.

The plots on the left show how the ionization state of oxygen changes with different amounts of light. Where the plot is dark blue the oxygen has all of its electrons, and going through lighter shades of blue and greens more electrons are ejected, until yellow where the oxygen has been fully ionized and there are no more electrons. From top-to-bottom, left-to-right the amount of light shining through a cloud is reduced, and you can see the amount of fully ionized oxygen (yellow) decreases and the unionized oxygen (dark blue) increases.

I looked at eight different ions of four different elements and found that there could be quite large changes (as much as a 50% increase) in the masses present, but that it would actually be quite hard to observe this difference. This is because the current assumption that all gas is at the same metallicity isn't a bad guess. However, there are regions in galaxies where this isn't true so it is useful to continue researching how this would effect our knowledge of galaxies.

If you're interested, you can find out more about my project in the report.

As a treat, I've included some more examples of simulated galaxies below.